The Comics Code Authority (CCA) was formed in 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America as an alternative to government regulation, to allow the comic publishers to self-regulate the content of comic books in the United States. Its code, commonly called "the Comics Code," lasted until the early 21st century. Many have linked the CCA's formation to a series of Senate hearings and the publication of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent.

Members submitted comics to the CCA, which screened them for adherence to its Code, then authorized the use of their seal on the cover if the book was found to be in compliance. At the height of its influence, it was a de facto censor for the U.S. comic book industry.

By the early 2000s, newer publishers bypassed the CCA and Marvel Comics abandoned it in 2001. By 2010, only three major publishers still adhered to it: DC Comics, Archie Comics, and Bongo Comics. Bongo broke with the CCA in 2010. DC and Archie followed in January 2011, rendering the Code defunct...

The Modern Age of Comic Books is an informal name for the period in the history of mainstream American comic books generally considered to last from the mid-1980s until present day.[1] During this period, comic book characters generally became darker and more psychologically complex, creators became better-known and active in changing the industry, independent comics flourished, and larger publishing houses became more commercialized.

Developments !!!!

Because the time period encompassing the Modern Age is not well defined, and in some cases disputed by both fans and most professionals, a comprehensive history is open to debate. Many influences from the Bronze Age of Comic Books would overlap with the infancy of the Modern Age. The work of creators such as John Byrne (Alpha Flight, Fantastic Four), Chris Claremont (Iron Fist, Uncanny X-Men), and Frank Miller (Daredevil) would reach fruition in the Bronze Age but their impact was still felt in the Modern Age. The Uncanny X-Men is the most definitive example of this impact as Bronze Age characters such as Wolverine and Sabretooth would have a huge influence on the Marvel Universe in the 1980s and beyond.

For DC, Crisis on Infinite Earths is the bridge that joins the two ages together. The result was the cancellation of The Flash (with issue 350), Superman (with issue 423), and Wonder Woman (with issue 329). The post-Crisis world would have Wally West as the new Flash, John Byrne writing a brand-new Superman series, and George Pérez working on a new Wonder Woman series. Batman would also get a makeover as the Batman: Year One storyline would be one of the most popular Batman stories ever published, with an animated adaptation of Year One released in 2011.

In rough chronological order by the beginning of the trend, here are some important developments that occurred during the Modern Age, many of which are interrelated:

Rise of independent publisher !!!!!

The late 1970s saw famed creators going to work for new independent publishers. The arrival of Jim Shooter as Editor in Chief at Marvel Comics saw the departure of key creators at Marvel such as Steve Gerber, Marv Wolfman, and others. In these new companies (Pacific, Eclipse, First) creators were free to create very personal stories. Mike Grell's Jon Sable Freelance, Howard Chaykin's American Flagg!, Mike Baron and Steve Rude's Nexus, Dave Steven's Rocketeer and John Ostrander's GrimJack attracted some attention and garnered a number of awards. These creators were brought in by DC editor Mike Gold to create defining works such as Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters by Grell, Blackhawk by Chaykin, and Hawkworld by Truman. With Alan Moore, Frank Miller, and Art Spiegelman's Maus (which would later receive the Pulitzer Prize), this period marks the summit of the artform per comics expert Scott McCloud.

Fantasy and horro !!!!

The Comics Code Authority was established in 1954, and specified that no comic should contain the words 'horror' or 'terror' in its title. This led EC Comics to abandon its horror comics line. Publishers such as Dell and Gold Key comics did run an expanding line of silver-age horror and "mystery" titles during the early 1960s, and Charlton maintained a continuous publishing history of them, during the later 1960s, a gradual loosening of enforcement standards eventually led to the re-establishment of horror titles within the DC and Marvel lineups by the end of the decade. Since this genre's evolution does not neatly match the hero-dominated transitional phases that are usually used to demarcate different eras of comic books, it is necessary to understand this "silver age" and "bronze age" background. 1970s horror anthology series merely continued what had already been established during the late 1960s, and endured into the 1980s until they were markedly transformed into new formats, many of which were greatly influenced by, or directly reprinted, "pre-code" content and styles of the early 1950s.

Starting with Alan Moore’s groundbreaking work on DC's Swamp Thing in the early 1980s, horror comic books incorporated elements of science fiction/fantasy and strove to a new artistic standard. Other examples include Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman (followed a few years later by Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Preacher). DC’s Vertigo line, under the editorship of Karen Berger, was launched in 1993, with the goal of specializing in this genre. Existing titles such as Animal Man, Doom Patrol, Hellblazer, and Shade, the Changing Man were absorbed into this new line. Other titles later were created for the line, which continued successfully into the 2010s.

Starting in the 1990s and throughout the 2000s, a number of successful movie adaptations of comic books, partly due to improvements in special effect technology, helped to extend their market audience, attracting the attention of many new readers who previously had not been interested in comic books. This also lead to an avalanche of other comic book adaptations which included previously lesser known Vertigo titles, notably Constantine (based on the comic book Hellblazer) and V for Vendetta.

The rise of anti-heroes !!!!

In the mid-1970s, Marvel antiheroes such as the X-Men’s Wolverine, the Punisher, and writer/artist Frank Miller’s darker version of Daredevil challenged the previous model of the superhero as a cheerful humanitarian. Miller also created Elektra, who straddled the conventional boundary between love interest and villain.

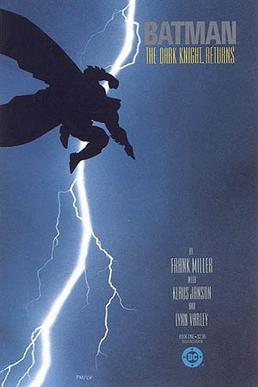

Two artistically influential DC Comics limited series contributed to the trend: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, also by Frank Miller and Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, both of which were series of psychological depth that starred troubled heroes.

By the late 1980s DC has published many mature titles such as Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, and Lobo. They featured morally ambiguous characters such as the cynical John Constantine and the violence loving Lobo with graphic violence and adult content that differentiated them from other mainstream titles. DC later separated these titles to their launched Vertigo imprint that publishes titles outside of the DC Universe.

By the early 1990s, antiheroes had become the rule rather than the exception, and among the most popular were Marvel Comics' Cable and Venom and Image Comics' Spawn.

The trend of creating characters with more psychological depth that were less black-and-white, also affected supervillains. For example, the Joker, Batman's nemesis, was portrayed less as an evil criminal and more as a mentally ill psychopath who can't control his actions, Marvel Comics' galactic planet-eater Galactus became a force of nature who means no personal malice in his feedings, and the X-Men's nemesis Magneto became more benign and sympathetic as a man who fights for an oppressed people, albeit through means others deem unacceptable.

Development of the X-Men franchise !!!!!

By the mid-1980s, X-Men had become one of the most popular titles in comics. Marvel decided to build on this success by creating a number of spin-off titles, sometimes collectively referred to as "X-Books". These early X-Books included New Mutants (which would later become X-Force), X-Factor, Excalibur, and a Wolverine solo series. There were many new popular additions to the X-Men in the 1990s, including Cable, and Bishop.

By the early 1990s, X-Men had become the biggest franchise in comics, and by the middle of the decade over a dozen X-Men-related comic books, both continuing and limited series, were published each month. On an almost annual basis from 1986 until 1999, one storyline crossed-over into almost every X-Book for two to three months. These "X-Overs" usually led to a spike in sales.

This sales boom resulted in a great deal of merchandising, such as action figures, video games and trading cards. This success was thanks in no small part to the Fox Network's animated X-Men series, which debuted in 1992 and drew in a large number of younger fans.

The sales boom began to wane in the mid to late 1990s, due to the crash of the speculators' market and the effect it had on the industry. Marvel declared bankruptcy in 1996,[3] and as a result, scaled back all of their franchises, including X-Men. A number of "X-books" were canceled, and the amount of limited series published, as well as general merchandise, was reduced.

In the early 2000s, a series of blockbuster X-Men movies have kept the X-Men franchise healthy, and have resulted in a larger market presence outside of comics. In 1999-2000, a new animated series, X-Men: Evolution debuted, while new toys have been developed and sold since the success of the first X-Men feature film. The comic books themselves have been reinvented in series such as Grant Morrison's New X-Men and the Ultimate X-Men, which, like Marvel's other "Ultimate" series, is an alternate universe story, starting the X-Men tale anew. This was done for X-Men, and other books, because Marvel feared that the long and complex histories of the established storylines of certain titles were scaring off new readers.

Effect on other comics !!!!

Many series tried to imitate the model the X-Men carved as a franchise. Marvel and DC expanded popular properties, such as Punisher, Spider-Man, Batman, and Superman into networks of spin-off books in the mid-to-late 1980s. Like the X-Books, some of these spin-offs highlighted a concept or supporting character(s) from a parent series, while others were simply additional monthly series featuring a popular character. In another similarity to the X-Books, these franchises regularly featured crossovers, where one storyline overlapped into every title in the “family” for a few months.

With regards to storylines overlapping, the Superman stories from 1991–2000 were written on a weekly basis. One needed to buy Superman, Adventures of Superman, Action Comics, and Superman: The Man of Steel (and eventually, Superman: The Man of Tomorrow) to keep up with any existing storylines. If a collector only bought Action Comics, they would only get twenty-five percent of the story. A triangle was featured on the cover of every Superman title with a number on it. This number indicated which week of the year the Superman title was released.

Makeovers and universe reboot !!!

Complementing the creation of these franchises was the concept of redesigning the characters. The Modern Age of comics would usher in this era of change. The impact of Crisis on Infinite Earths was the first example as Supergirl died in issue 7, and long-time Flash (Barry Allen) died in issue 8. Specifically, Barry Allen signified the beginning of the Silver Age of Comics and his death was highly shocking at the time. Marvel Comics' Secret Wars would usher in a new change as well as Spider-Man would wear a black costume. This costume change led to the development of the character Venom.

The interest in the speculator market of a new Spider-Man costume led to other changes for Marvel characters in the 1980s. Iron Man would have a silver and red armor in issue 200. Captain America would be fired and would be reborn as the Captain, wearing a black outfit in issue 337 of the series. The Incredible Hulk would revert to his original grey skin color in issue 325. Issue 300 of the first Avengers series resulted in a new lineup including Mister Fantastic and the Invisible Woman, of the Fantastic Four. Within the decade, Wolverine would switch to a brown and yellow costume, Thor would be replaced by Thunderstrike, Archangel would emerge as the X-Men's Angel's dark counterpart after serving as one of Apocalypse's Horsemen, and many other Marvel characters would have complete image overhauls. The changes to Spider-Man, Thor, Captain America, Iron Man, Wolverine and most other Marvel characters would be undone in the early 1990s.

The 1990s would bring similar changes to the DC Universe, including the death of Superman in 1992[4] and the crippling of Bruce Wayne in 1993.[5] The only lasting change was Kyle Rayner replacing Hal Jordan as Green Lantern.

In addition to individual character or franchise/family wide makeovers, Crisis on Infinite Earths ushered in a popular trend of "rebooting," "remaking," or greatly reimagining the publisher-wide universes every 5–10 years on varying scales. This often resulted in origins being retold, histories being rewritten, and so forth. These reinventions could be on as large a scale as suddenly retconning seminal story points and rewriting character histories, or simply introducing and/or killing off/writing out various important and minor elements of a universe. Crisis on Infinite Earths resulted in several miniseries which explicitly retconned character histories, such as Batman: Year One, Superman: Man of Steel, and Wonder Woman: Gods and Mortals. An example of a less ambitious scale of changes is Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters, which did not explicitly retcon or retell Green Arrow's history, but simply changed his setting and other elements of the present, leaving the past largely intact. This trend of publisher wide reinventions, which often consists of a new miniseries and various spinoff storylines in established books, continued for decades, with DC's New 52 in 2011 and Marvel's Secret Wars in 2015.

Image Comics and creator rights disputes[edit]

In the mid-1980s, artist Jack Kirby, co-creator of many of Marvel's most popular characters, came into dispute with Marvel over the disappearance of original pages of artwork from some of his most famous titles. Alan Moore, Frank Miller, and many other contemporary stars became vocal advocates for Kirby.

By the early 1990s, these events, as well as the influence of vocal proponents of independent publishing, helped to inspire a number of Marvel artists to form their own company, Image Comics, which would serve as a prominent example of creator-owned comics publishing. Marvel artists such as X-Men’s Jim Lee, The New Mutants/X-Force’s Rob Liefeld and Spider-Man’s Todd McFarlane were extremely popular and were idolized by younger readers in ways more common to professional athletes and rock musicians than comic book artists. Propelled by star power and upset that they did not own the popular characters they created for Marvel, several illustrators, including the above three formed Image Comics in 1992, an umbrella label under which several autonomous, creator-owned companies existed.[6] Image properties, such as WildC.A.T.s, Gen¹³, Witchblade and especially McFarlane’s Spawn provided brisk competition for long-standing superheroes. Image in particular is singled out by some critics for contributing to the conditions which led to the speculator market crashing, as Image titles favored alternative covers, foil covers, and other "collectible" comics.[7]

Many popular creators followed Image's lead and attempted to use their star power to launch their own series; ones for which they would have licensing rights and editorial control. Chris Claremont, famous for his long run as the writer of Uncanny X-Men, created Sovereign Seven for DC; Joe Madureira, also made popular by Uncanny X-Men, launched Battle Chasers for WildStorm Productions; and Kurt Busiek, Alex Ross, and Brent Anderson created Astro City for Image.

Milestone Comics and racial diversity!!!!!!!

In 1993, a coalition of African-American writers and artists started Milestone Comics, believing that minority characters were underrepresented in American superhero comics. Some of the company's better-known series include Static, about an African-American teen who became Milestone's key character, Hardware, an example of Afrofuturism, Icon, about an alien mimicking the appearance of an African-American, and Blood Syndicate, a series about a multicultural gang of superheroes. All of these flagship titles were co-created by Dwayne McDuffie. In 1997, the Milestone Universe merged with the DC Universe.

The rise and fall of the speculator market !!!!!!

By the late 1980s, important comic books, such as the first appearance of a classic character or first issue of a long-running series, were sold for thousands of dollars. Mainstream newspapers ran reports that comic books were good financial investments and soon collectors were buying massive amounts of comics they thought would be valuable in the future.

Publishers responded by manufacturing collectors’ items, such as trading cards, and “limited editions” of certain issues featuring a special or variant cover. The first issues of Marvel Comics' X-Force, X-Men vol. 2, and Spider-Man became some of the first and most notorious examples of this trend. Another trend which emerged was foil-stamped covers. The first Marvel comic book with a foil-stamped cover was the third volume of the Silver Surfer, issue 50 (June 1991). A glow-in-the-dark cover for Ghost Rider, volume 3, issue 15 appeared as well. This led a market boom, where retail shops and publishers made huge profits and many companies, large and small, expanded their lines. Image Comics in particular became notorious for this, with many of its series debuting with alternative covers, wide use of embossed and foil covers and other "collectible" traits.

This trend was not confined to the books themselves, and many other pieces of merchandise, such as toys, particularly "chase" action figures (figures made in smaller runs than others in a particular line), trading cards, and other items, were also expected to appreciate in value. McFarlane Toys was notable for this, as it created many variations in its high-quality toys, most of which were main characters or occasional guest stars in the Spawn series.

But few, in the glut of new series, possessed lasting artistic quality and the items that were predicted to be valuable did not become so, often because of huge print runs that made them commonplace. The speculator market began to collapse in summer 1993 after Turok #1 (sold without cover enhancements) badly underperformed and Superman's return in Adventures of Superman #500 sold less than his death in Superman #75, something speculators and retailers had not expected. Companies began expecting a contraction and Marvel UK's sales director, Lou Marks, stated in September 29 that retailers were saying there was "simply no room to display all the comics being produced".[8] The resulting crash devastated the industry: sales plummeted, hundreds of retail stores closed and many publishers downsized. Marvel made an ill-judged decision during the crash to buy Heroes World Distribution to use as its own exclusive distributor,[9] which resulted in both distribution problems for Marvel and the industry's other major publishers making exclusive distribution deals with other companies, which would lead to Diamond Comic Distributors Inc. becoming the only distributor of note in North America.[10][11] In 1996, Marvel Comics, the largest company in the industry and hugely profitable just three years before, declared bankruptcy (it has since rebounded).

The crash also marked the relative downfall of the large franchises, inter-connected "families" of titles that lead to a glut of merchandising. While the big franchise titles still have a large amount of regular titles and merchandising attached to them, all of these things were notably scaled back after the crash. Several franchises have once again gained prominence, such as the X-Men, due in large part to the feature films X-Men and X2, and many DC heroes thanks to the success of various animated series' based on their characters, such as Justice League, Justice League Unlimited, and Teen Titans.

The rise of the trade paperback format !!!!!

Although sales of comic books dropped in the late 1990s and the early 2000s, sales rose for trade paperbacks, collected editions in which several issues are bound together with a spine and often sold in bookstores as well as comic shops. In addition, the publishing format has gained such respectability as literature that it became an increasingly prominent part of both book stores and public library collections.

Some series were saved from cancellation solely because of sales of trade paperbacks, and storylines for many of the most popular series of today (DC’s JLA and various Batman series and Marvel’s Ultimate Spider-Man and New X-Men) are put into trade paperback instantly after the storyline ends.

Trade paperbacks are often even given volume numbers, making them a serializations of sorts. Due to this, many writers now consider their plots with the trade paperback edition in mind, scripting stories that last four to twelve issues, which could easily be read as a "graphic novel."

The popularity of trade paperbacks, has resulted in older material being reprinted as well. The Essential Marvel line of trade paperbacks has reprinted heroes such as Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four and has been able to introduce these Silver Age stories to a new generation of fans. These editions tend to resemble a phone book in that these are very thick books and are black-and-white (to help keep the cost down).

DC Comics has followed suit by introducing a line called Showcase Presents. The first four have included Superman, Green Lantern, Jonah Hex, and Metamorpho the Elemental Man. Other characters have included Green Arrow, The Superman Family, the Teen Titans and the Elongated Man.

Comics creators' mainstream success !!!!

|

|

While many comic book artists and writers had become well known by their readership as early as the 1940s, some comics creators in the late 1980s and the 1990s became known to the general population. These included Todd McFarlane, Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, and Frank Miller. Some, such as Gaiman, went on to write critically and commercially successful novels. Others, like Miller, became Hollywood screenwriters and directors.

Conversely, film and TV directors and producers became involved with comics. J. Michael Straczynski, creator of TV's Babylon 5, was recruited to write Marvel Comics' The Amazing Spider-Man and, later Fantastic Four filmmaker Reginald Hudlin became the writer of Marvel's Black Panther. Joss Whedon, creator of TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer, wrote Marvel's Astonishing X-Men and Runaways, among other series. Richard Donner, who directed the Superman films of the 1970s and 1980s, became a writer on the Superman feature in Action Comics in 2006, co-writing with comics writer (and Donner's former production assistant) Geoff Johns. Paul Dini, producer and writer of Batman: The Animated Series and Superman: The Animated Series, started writing for DC in 1994 on special projects and took the helm as writer of Detective Comics in 2006.

Comics writer Peter David's career as a novelist developed concurrently with his comic-book career.[12][13] Sandman writer Neil Gaiman has also enjoyed success as a fantasy writer and number one New York Times Bestseller. Michael Chabon who won the Pulitzer Prize with The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, a novel about the start of the Golden Age of Comic Books, then went on to write comics for DC and Dark Horse. Novelist Brad Meltzer saw success in the comics field with the controversial miniseries Identity Crisis, as well as runs on Green Arrow and Justice League of America.

In the late 2000s, Corey Blake's Round Table Press have converted novels, such as The Long Tail and The Art of War, among others, into comic book format.[14][15]

The influence of Japanese comics and animation!!!

The mid to late 1980s would see the quiet introduction of various translated Japanese manga into North America. While not the first company to release translated manga, the first company to do so to a large degree was Eclipse which introduced Area 88, Legend of Kamui, and Mai the Psychic Girl, the three titles that are generally associated with the first wave of manga translated into English. Along with Comico and Eternity Comics's adaptation of the Robotech animated series, various other companies would release manga style comics such as Ben Dunn's Ninja High School and Barry Blair's Samurai. Dark Horse Comics would release many translated manga during the 1990s. Marvel's Epic Comics line would also license an English translation of Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira. As of the 2010s, most translated manga are distributed by subsidiaries of the original Japanese property owners, such as Kodansha, Shogakukan or Bandai. While manga translations were previously presented in the traditional American comic magazine format, the digest size publications traditional to manga has become common. In some cases, the books are presented in the original form intended to be read from right to left. Tokyopop was the first company to contract non-Japanese artists to produce and market (Original English-language manga). OELs are original material written by non-Japanese authors who directly emulate manga style in both storytelling and art and openly identify their works as manga. Previous manga-style comics consisted mostly of selective borrowing of manga or anime elements for a work that nevertheless is not intended to be regarded as manga.

The Bronze Age of Comic Books is an informal name for a period in the history of mainstream American comic books usually said to run from 1970 to 1985. It follows the Silver Age of Comic Books,[1] and is followed by the Modern Age of Comic Books.

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and more socially relevant storylines (akin to those found in the Golden Age of Comic Books) featuring real-world issues, such as racism, drug use, alcoholism, urban poverty, and environmental pollution, began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age of Comic Books.

Origins!!!!

There is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character. The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams (inking was by Adams or Dick Giordano), focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.[2][3]

Later in 1970, Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, ending arguably the most important creative partnership of the Silver Age (with Stan Lee). Kirby then turned to DC, where he created The Fourth World series of titles starting with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 in December 1970. Also in 1970 Mort Weisinger, the long term editor of the various Superman titles, retired to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite—by then—powers, which was done by veteran Superman artist Curt Swan together with ground-breaking author Denny O'Neil.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their super-hero publications, cancelling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres such as horror and sword-and-sorcery.[citation needed]

The era also encompassed major changes in the distribution of and audience for comic books. Over time, the medium shifted from cheap mass market products sold at newsstands to a more expensive product sold at specialty comic book shops and aimed at a smaller, core audience of fans. The shift in distribution allowed many small-print publishers to enter the market, changing the medium from one dominated by a few large publishers to a more diverse and eclectic range of books.[citation needed]

The 1970s !!!!!

In 1970, Marvel published the first comic book issue of Robert E. Howard's pulp character Conan the Barbarian. Conan's success as a comic hero resulted in adaptations of other Howard characters: King Kull, Red Sonja, and Solomon Kane. DC Comics responded with comics featuring Warlord, Beowulf, and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. They also took over the licensing of Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan from long-time publisher Gold Key and began adaptating other Burroughs creations, such as John Carter, the Pellucidar series, and the Amtor series. Marvel also adapted to comic book form, with less success, Edwin Lester Arnold's character Gullivar Jones and, later, Lin Carter's Thongor.

The murder of Spider-Man's longtime girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, at the hands of the Green Goblin in 1973's Amazing Spider-Man #121-122 is considered by comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg to be the definitive Bronze Age event, as it exemplifies the period's trend towards darker territory and willingness to subvert conventions such as the assumed survival of long-established, "untouchable" characters. However, there had been a gradual darkening of the tone of superhero comics for several years prior to "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", including the death of her father in 1970's Amazing Spider-Man #90 and the beginning of the Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams tenure on Batman.

In 1971, Marvel Comics Editor-in-Chief Stan Lee was approached by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story, "Green Goblin Reborn!," which portrayed drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. At that time, any portrayal of drug use in comic books was banned outright by the Comics Code Authority, regardless of the context. The CCA refused to approve the story, but Lee published it regardless.

The positive reception that the story received led to the CCA revising the Comics Code later that year to allow the portrayal of drug addiction as long as it was depicted in a negative light. Soon after, DC Comics had their own drug abuse storyline in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85-86. Written by Denny O'Neil with art by Neal Adams, the storyline was entitled "Snowbirds Don't Fly," and it revealed that the Green Arrow's sidekick Speedy had become addicted to heroin.

The 1971 revision to the Comics Code has also been seen as relaxing the rules on the use of vampires, ghouls and werewolves in comic books, allowing the growth of a number of supernatural and horror-oriented titles, such as Swamp Thing, Ghost Rider and The Tomb of Dracula, among numerous others. However, the tone of horror comic stories had already seen substantial changes between the relatively tame offerings of the early 1960s (e.g. Unusual Tales) and the more violent products available in the late 1960s (e.g. The Witching Hour, revised formats in House of Secrets, House of Mystery, The Unexpected).

At the beginning of the 1970s, publishers moved away from the super-hero stories that enjoyed mass-market popularity in the mid-1960s; DC cancelled most of its super-hero titles other than those starring Superman and Batman, while Marvel cancelled weaker-selling titles such as Dr. Strange, Sub-Mariner and The X-Men. In their place they experimented with a wide variety of other genres, including Westerns, horror and monster stories, and the above-mentioned adaptations of pulp adventures. These trends peaked in the early 1970s, and the medium reverted by the mid-1970s to selling predominantly super-hero titles.[citation needed]

Further developments !!!!

Social relevance !!!!!

A concern with social issues had been a part of comic book stories since their beginnings: early Superman stories, for example, dealt with issues such as child abuse and working conditions for minors. However, in the 1970s relevance became not only a feature of the stories, but something that the books loudly proclaimed on their covers to promote sales. The Spider-Man drug issues were at the forefront of the trend of "social relevance" - comic books handling real-life issues. The above-mentioned Green Lantern/Green Arrow series dealt not only with drugs, but other topics like racism, income inequality, political corruption, and environmental degradation. The X-Men titles, which were partly based on the premise that mutants were a metaphor for real-world minorities, became wildly popular. Other well-known "relevant" comics include the "Demon in a Bottle", where Iron Man confronts his alcoholism, and the socially conscious stories written by Steve Gerber in such titles as Howard the Duck and Omega the Unknown. Issues regarding female empowerment became trends with female versions of popular male characters (Spider-Woman, Red Sonja, Ms. Marvel, She-Hulk).

While the larger trend eventually faded, contemporary social commentary has remained in superhero stories to this day.[citation needed]

Creator credit and labor agreements!!!!!

Writers and artists began getting a lot more credit for their creations even though they were still ceding copyrights to the companies for whom they worked. Pencil Artists were allowed to keep their original artwork and sell it on the open market. When word got out that Superman's creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were living in poverty, artists such as Neal Adams, Jerry Robinson, and Bernie Wrightson helped organize fellow artists to pressure DC in rectifying them and other pioneers from the 1930s and 1940s. Newer publishers, such as Pacific Comics and Eclipse Comics, negotiated contracts in which creators retained copyright to their creations.

Minority superheroes !!!!!

One of the most significant developments during the period was a substantial rise in the number of black and other minority superheroes. Before the 1970s, there had been very few non-white superheroes (the Black Panther and the Falcon being notable exceptions) but starting in the early 1970s this began to change with the introduction of characters such as Marvel's Luke Cage (who was the first black superhero to star in his own comic book in 1972, followed a year later by Black Panther in Jungle Action), Storm, Blade, and Monica Rambeau, and DC's Green Lantern John Stewart, Bronze Tiger, Black Lightning, Vixen, and Cyborg.

Characters such as Luke Cage, Mantis, Misty Knight, Shang-Chi, and Iron Fist have been seen by some as an attempt by Marvel Comics to cash in on the 1970s crazes for Kung Fu movies. However, these and other minority characters came into their own after these film trends faded, and became increasingly popular and important as time progressed. By the mid-1980s, Storm and Cyborg had become leaders of the X-Men and Teen Titans respectively, and John Stewart briefly replaced Hal Jordan as the lead character of the Green Lantern title.

Art styles !!!!!!

Starting with Neal Adams' work in Green Lantern/Green Arrow a new sophisticated realism became the norm in the industry. Buyers would no longer be interested in the heavily stylized work of artists of the Silver Age or simpler cartooning of the Golden Age. The so-called "House Styles" of DC and Marvel became imitations of Adams' work and more realistic versions of Kirby's respectively. This change is sometimes credited to a new generation of artists influenced by the popularity of EC Comics in the 1950s. In spite of the House Styles, those artists who could draw apart from these would gain some notoriety. Such names include Berni Wrightson, Jim Starlin, John Byrne, Frank Miller, George Pérez, and Howard Chaykin. A secondary line of comics at DC, headed by former EC Comics artist Joe Orlando and devoted to horror titles, established a differing set of styles and aggressively sought talent from Asia and Latin America.[citation needed]

The revival of the X-Men and the Teen Titans !!!!!

The X-Men were originally created in 1963 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. However, the title never achieved the popularity of other Lee/Kirby creations, and by 1970 Marvel ceased publishing new material and the title was turned over to reprints. However, in 1975 an "all-new all-different" version of the X-Men was introduced by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum in Giant-Size X-Men #1, with Chris Claremont as uncredited assistant co-plotter.[4] Claremont stayed as writer on just about all X-Men related titles, including spinoffs, for the next sixteen years, after which other regular writers such as Louise Simonson, Fabian Nicieza, and Scott Lobdell joined and Claremont eventually left.

One of the most apparent influences from this series was the creation of what became DC Comics' answer to X-Men's character-based storytelling style, The New Teen Titans by Marv Wolfman and George Pérez, which became a highly successful and influential property in its own right. Wolfman would associate himself with the title for sixteen years, while Perez established a large fanbase and sought-after pencilling style. A successful cartoon based on the Titans of the Bronze Age of Comics was launched in 2003, and lasted for three years.

Team-up books and anthologies !!!!!!!

During the Silver Age, comic books frequently had several features, a form harkening back to the Golden Age when the first comics were anthologies. In 1968, Marvel graduated its double feature characters appearing in their anthologies to full-length stories in their own comic. But several of these characters could not sustain their own title and were cancelled. Marvel tried to create new double feature anthologies such as Amazing Adventures and Astonishing Tales which did not last as double feature comic books. A more enduring concept was that of the team-up book, either combining two characters, at least one of which was not popular enough to sustain its own title (Green Lantern/Green Arrow, Super-Villain Team-Up, Power Man and Iron Fist, Daredevil and the Black Widow, Captain America and the Falcon) or a very popular character with a guest star of the month (Marvel Team-Up and Marvel Two-in-One). Even DC combined two features in Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes and had team-up books (The Brave and the Bold, DC Comics Presents and World's Finest Comics). Virtually all such books disappeared by the end of the period.

Company crossovers !!!!!!

Marvel and DC worked out several crossover titles the first of which was Superman vs the Amazing Spider-Man. This was followed by Batman vs. Hulk, a second Superman and Spider-Man, and the X-Men vs The New Teen Titans. Another title, The Avengers vs The Justice League of America was written by Gerry Conway and drawn by George Pérez with plotting by Roy Thomas but was never published, reflecting the later animosity between the two companies. Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter was not pleased that DC wanted the fourth company crossover to include the New Teen Titans, DC's best-selling title at the time, as he wanted the crossover to be the X-Men and the Legion of Super-Heroes. This led to Shooter's decision to stall and cancel the JLA/Avengers project.[citation needed]

Reprints !!!!!!

Beginning circa 1970, Marvel introduced vast numbers of reprints into the market, which played a key role in their becoming the overall market leader among comic publishers. Suddenly many titles featured reprints: X-Men, Sgt. Fury, Kid Colt Outlaw, Rawhide Kid, Two-Gun Kid, Outlaw Kid, Jungle Action, Special Marvel Edition (the early issues), War is Hell (the early issues), Creatures on the Loose, Monsters on the Prowl, and FEAR, to name just a few.

DC Implosion !!!!!!!!

In the mid-'70s, DC launched numerous new titles such as Jack Kirby's New Gods and Steve Ditko's Shade the Changing Man. The company referred to this as the "DC Explosion". However, DC greatly overestimated the appeal of so many new titles at once, and it nearly broke the company and the industry, including Charlton Comics. Jenette Kahn would eventually take the helm of the company.

Marvel eventually gained 50% of the market and Stan Lee handed control of the comic division to Jim Shooter while he worked with their growing animation spin-offs.

Non-superhero comics !!!!!!!

As the Bronze Age began in the early 1970s, popularity shifted away from the established superhero genre towards comic book titles from which superheroes were absent altogether. These non-superhero comics were typically inspired by genres like Westerns or fantasy & pulp fiction. As previously noted, 1971's revised Comics Code left the horror genre ripe for development and several supernaturally-themed series resulted, such as the popular The Tomb of Dracula, Ghost Rider, and Swamp Thing. In the science fiction genre, post-apocalyptic survival stories were an early trend, as evidenced by characters like Deathlok, Killraven, and Kamandi. The long-running sci-fi/fantasy anthology comic magazine Metal Hurlant and its American counterpart Heavy Metal began publishing in the late '70s. Marvel's related comic series was very popular with a nine-year run.

Other titles began from characters originally found in 20th century pulp magazines or novels. Noteworthy examples are the long running titles Conan the Barbarian and Savage Sword of Conan (the later was published as a magazine, bypassing the Comics Code), as well as Master of Kung-Fu. The early success of these titles soon led to more pulp character adaptations (Doc Savage, Kull, The Shadow, Justice, Inc., Tarzan). During this period, both Marvel and DC also regularly published official comic book adaptations for various projects, including popular movies (Planet of the Apes, Godzilla, Logan's Run, Indiana Jones, Jaws 2, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars), TV shows (The Man From Atlantis, Battlestar Galactica, Star Trek, The A Team, Welcome Back Kotter), toys (G.I. Joe, Micronauts, Transformers, Rom, Atari Force, Thundercats), and even public figures (Kiss, Pope John Paul II).

Though not necessarily "non-superhero", a few unconventional comic book series from the period featured one or more villains as their central character (Super-Villain Team-Up, Secret Society of Super-Villains, The Joker).

Alternate markets and formats !!!!!!!!!

Archie Comics dominated the female market during this time with their characters, Betty and Veronica having some of the largest circulation of titular female characters. Several clones were attempted by Marvel and DC unsuccessfully. Several Archie titles examined socially relevant issues and introduced a few African-American characters. Archie largely switched to paperback digest format in the late 1980s.

Children's comics were still popular with Disney reprints under the Gold Key label along with Harvey's stable of characters which grew in popularity. The latter included Richie Rich, Casper, and Wendy Witch, which eventually switched to digest format as well. Again Marvel and DC were unable to emulate their success with competing titles.

An 'explicit content' market akin to the niche Underground Comix of the late '60s was ostensibly opened with the Franco-Belgian import Heavy Metal Magazine. Marvel launched competing magazine titles of their own with Conan the Barbarian and Epic Magazine which would eventually become its division of Direct Sales comics.

The paper drives of World War II and a growing nostalgia among Baby-Boomers in the 1970s made comic books of the 1930s and 1940s extremely valuable. DC experimented with some large size paperback books to reprint their Golden Age comics, create one-shot stories such as Superman vs. Shazam and Superman vs. Muhammad Ali as well as the early Marvel crossovers.

The popularity of those early books also opened up a market for specialty shops. The existence of these shops made it possible for small-press publishers to reach an audience, and some comic book artists began self-publishing their own work. Notable titles of this type included Dave Sim's Cerebus and Wendy and Richard Pini's Elfquest series. Other small-press publishers came in to take advantage of this growing market: Pacific Comics introduced in 1981 a line of books by comic-book veterans such as Jack Kirby, Mike Grell and Sergio Aragonés, for which the artists retained copyright and shared in royalties.

In 1978, Will Eisner published his "graphic novel" A Contract With God, an attempt to produce a long-format story outside the traditional comic book genres. In the early 1980s Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly began publishing Raw Magazine, which included the early serialization of Spiegelman's award-winning graphic novel Maus.

Comics sold on newsstands were distributed on the basis that unsold copies were returned to the publisher. Comics sold to comic shops were sold on a no-return basis. This allowed small-press titles sold through the direct market to keep publishing costs down and increase profits, making viable titles that otherwise would have been unprofitable. Marvel and DC began taking advantage of this direct market themselves, publishing books and titles distributed only through comic book shops.

Disappearing genres !!!!!!!!

This period is also marked by the cancellation of most titles in the genres of romance, western and war stories that had been a mainstay of comics production since the forties. Most anthologies, whether they presented feature characters or not, also disappeared. They had been used since the Golden Age to create new characters, to host characters that lost their own title or to feature several characters. This had the effect of standardizing the length of comics stories within a narrow range so that multiple stand-alone stories would appear within a single issue. The underground comix of the 1960s counterculture continued, but contracted significantly and were ultimately subsumed into the emerging direct market.

End of the Bronze Age !!!!!!!

One commonly used ending point for the Bronze Age is the 1985-1986 time frame. As with the Silver Age, the end of the Bronze Age relates to a number of trends and events that happened at around the same time. At this point, DC Comics completed its special event, Crisis on Infinite Earths which marked the revitalization of the company's product line to become a serious market challenger to Marvel again. This time frame also includes the company's release of the highly acclaimed works, Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, which redefined the superhero genre and inspired years of "grim and gritty" comic books.

At Marvel Comics, the commonly used milestone marking the end of the Bronze Age is Secret Wars, although this could be extended to 1986 which saw the cancellation of Defenders and Power Man and Iron Fist, as well as the launch of the New Universe and X-Factor (extension of the X-Men franchise).

After the Bronze Age came the Modern Age of Comic Books, alternatively referred to as the Dark Age of Comic Books. According to Shawn O'Rourke of PopMatters, the shift from the previous ages involved a "deconstructive and dystopian re-envisioning of iconic characters and the worlds that they live in",[5] as typified by Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen (1986–1987). Other features that define the era are an increase in adult oriented content, the rise of the X-Men as Marvel Comics' "dominant intellectual property", and a reorganization in the industry's distribution system.[5] These changes would also lead to the appearance of new independent comic book publishers in the early 1990s - such as Image Comics, with titles like Spawn and Savage Dragon which also boasted a darker, sarcastic and more mature approach to superhero storylines.

Noted Bronze Age talents !!!!!!!!

NOTE: This is not a definitive list whatsoever. These are merely people who have represented a strong fan following and have been involved with some of the greatest and/or most influential projects of the Bronze Age.

Timeline of the Bronze Age !!!!!!!!

- January 1970: First Denny O'Neil/Neal Adams Batman story (The Secret of the Waiting Graves, Detective Comics #395) signals a darker era for the iconic character. Ward Dick Grayson (Robin) left for college, and alter ego Bruce Wayne left Wayne Manor, in previous month's Batman comic.

- April 1970: DC Comics adds Green Arrow to Green Lantern book for stories written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams featuring "relevance". Series, story, writer, penciller and inker all win first Shazam Awards in their respective categories the following year.

- October 1970: Marvel Comics begins publishing Conan The Barbarian.

- October 1970: DC Comics begins publishing Jack Kirby's Fourth World titles beginning with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen and continuing with New Gods, The Forever People and Mister Miracle.

- 1971: The Comics Code is revised.

- January 1971: Clark Kent becomes a newscaster at WGBS-TV.

- February 1971: African-American superhero Falcon shares co-feature status in renamed Captain America and The Falcon.

- July 1971: DC Comics introduces the character of Swamp Thing in its House of Secrets title.

- April 1972: Marvel begins publishing The Tomb of Dracula.

- June 1972: Luke Cage becomes the first African American superhero to receive his own series in Hero for Hire #1.

- June 1973: Green Goblin kills Gwen Stacy in Amazing Spider-Man #121.

- December 1973: The absurdist Howard the Duck makes his first appearance in comics and would be one of the most popular non-superheroes ever. He would get his own series in 1976 and he would graduate to his own daily newspaper strip and a 1986 film.

- February 1974: First appearance of the Punisher in The Amazing Spider-Man #129.

- November 1974: First appearance of Wolverine in Incredible Hulk #181.

- 1975: Giant-Size X-Men #1 by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum introduces the "all-new, all-different X-Men."

- July 1977: At the request of Roy Thomas, Marvel releases Star Wars, based on the hit movie, and it quickly becomes one of the best-selling books of the era.

- August 1977: Black Manta kills Aquababy in Adventure Comics #452.

- December 1977: Dave Sim launches Cerebus independent of the major publishers, the longest running limited series (300 issues) in comics as well as the longest run by one artist on a comic book series.

- Spring 1978: First appearance of Elfquest by Wendy and Richard Pini is published in Fantasy Quarterly.

- 1978: DC cancels over half of its titles in the so-called DC Implosion.

- July 1979: DC publishes The World of Krypton, the first comic book mini-series, which gave publishers a new flexibility with titles.

- November 1980: First issue of DC Comics' The New Teen Titans whose success at revitalizing a previously underperforming property would lead to the idea of revamping the entire DC Universe.

- June 1982: Marvel publishes Contest of Champions, its first limited series. This title features most of the company's major characters together, providing a template for later limited-series storylines at Marvel and DC.

- October 1982: Comico begins publishing a comic called Comico Primer that would later be the starting point for several influential artists and writers such as Sam Kieth and Matt Wagner.

- May 1984: Marvel begins releasing the first "big event" storyline, Secret Wars, which would, along with Crisis on Infinite Earths, popularize big events, and make them a staple in the industry.

- May 1984: Mirage Studios begins publishing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles by Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird.

- Summer 1984: DC Comics, desiring to feature more diverse characters, adds Vixen, Vibe (and Steel) to the Justice League of America, with Aquaman as team leader and later Batman. This was commonly known as "Justice League Detroit Era."

- April 1985: DC begins publishing Crisis on Infinite Earths, which would drastically restructure the DC universe, and popularize the epic crossover in the comics industry along with Secret Wars. In the aftermath of this Crisis, DC cancels and relaunches the Flash, Superman, and Wonder Woman.

- August 1985: Eclipse Comics publishes Miracleman, written by Alan Moore, developing the later trends of bringing superhero fiction into the real world, and showing the effects of immensely powerful characters on global politics (both potentially apocalyptic and utopian).

- 1986: DC publishes Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, setting a new grim tone for Batman.

- September 1986: Curt Swan, primary Superman artist during the Silver and Bronze Age, is retired from his monthly art duties on all Superman books after the last Pre-Crisis Superman story, called "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?," on which he worked together with Alan Moore, is published.

- September 1986-October 1987: DC Comics publishes the Watchmen limited series, seen by many as a model for a new age of comics.

Origin of the Silver Age...........

Comics historian and movie producer Michael Uslan traces the origin of the "Silver Age" term to the letters column of Justice League of America #42 (Feb. 1966), which went on sale December 9, 1965.[2] Letter-writer Scott Taylor of Westport, Connecticut wrote, "If you guys keep bringing back the heroes from the [1930s-1940s] Golden Age, people 20 years from now will be calling this decade the Silver Sixties!"[2] According to Uslan, the natural hierarchy of gold-silver-bronze, as in Olympic medals, took hold. "Fans immediately glommed onto this, refining it more directly into a Silver Age version of the Golden Age. Very soon, it was in our vernacular, replacing such expressions as ... 'Second Heroic Age of Comics' or 'The Modern Age' of comics. It wasn't long before dealers were ... specifying it was a Golden Age comic for sale or a Silver Age comic for sale."[2]

The Silver Age of Comic Books was a period of artistic advancement and commercial success in mainstream American comic books, predominantly those in the superhero genre. Following the Golden Age of Comic Books and an interregnum in the early to mid-1950s, the Silver Age is considered to cover the period from 1956 to circa 1970, and was succeeded by the Bronze and Modern Ages.[1] A number of important comics writers and artists contributed to the early part of the era, including writers Stan Lee, Gardner Fox, John Broome, and Robert Kanigher, and artists Curt Swan, Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Steve Ditko, Mike Sekowsky, Gene Colan, Carmine Infantino, John Buscema, and John Romita, Sr. By the end of the Silver Age, a new generation of talent had entered the field, including writers Denny O'Neil, Gary Friedrich, Roy Thomas, and Archie Goodwin, and artists such as Neal Adams, Herb Trimpe, Jim Steranko, and Barry Windsor-Smith.

The popularity and circulation of comic books about superheroes declined following World War II, and comic books about horror, crime and romance took larger shares of the market. However, controversy arose over alleged links between comic books and juvenile delinquency, focusing in particular on crime and horror titles. In 1954, publishers implemented the Comics Code Authority to regulate comic content. In the wake of these changes, publishers began introducing superhero stories again, a change that began with the introduction of a new version of DC Comics' The Flash in Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956). In response to strong demand, DC began publishing more superhero titles including Justice League of America, which prompted Marvel Comics to follow suit beginning with Fantastic Four #1. Silver Age comics have become collectible, with a copy of Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug. 1962), the debut of Spider-Man, selling for $1.1 million in 2011.

History !!!!!!!

Background........

Spanning World War II, when American comics provided cheap and disposable escapist entertainment that could be read and then discarded by the troops,[3] the Golden Age of comic books covered the late 1930s to the late 1940s. A number of major superheroes were created during this period, including Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, and Captain America.[4] In subsequent years comics were blamed for a rise in juvenile crime statistics, although this rise was shown to be in direct proportion to population growth.[citation needed] When juvenile offenders admitted to reading comics, it was seized on as a common denominator;[3] one notable critic was Fredric Wertham, author of the book Seduction of the Innocent (1954),[3] who attempted to shift the blame for juvenile delinquency from the parents of the children to the comic books they read. The result was a decline in the comics industry.[3] To address public concerns, in 1954 the Comics Code Authority was created to regulate and curb violence in comics, marking the start of a new era.

DC Comics !!!!!!

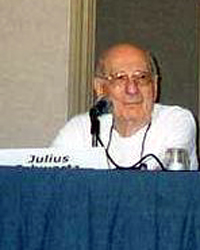

The Silver Age began with the publication of DC Comics' Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956), which introduced the modern version of the Flash.[5][6][7] At the time, only three superheroes—Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman—were still published under their own titles.[8] According to DC comics writer Will Jacobs, Superman was available in "great quantity, but little quality." Batman was doing better, but his comics were "lackluster" in comparison to his earlier "atmospheric adventures" of the 1940s, and Wonder Woman, having lost her original writer and artist, was no longer "idiosyncratic" or "interesting."[8] Jacobs describes the arrival of Showcase #4 on the newsstands as "begging to be bought," the cover featured an undulating film strip depicting the Flash running so fast that he had escaped from the frame.[9] Editor Julius Schwartz, writer Gardner Fox, and artist Carmine Infantino were some of the people behind the Flash's revitalization.[10] Robert Kanigher wrote the first stories of the revived Flash, and John Broome was the writer of many of the earliest stories.[11][12]

With the success of Showcase #4, several other 1940s superheroes were reworked during Schwartz' tenure, including Green Lantern, the Atom, and Hawkman,[13] as well as the Justice League of America.[10] The DC artists responsible included Murphy Anderson, Gil Kane and Joe Kubert.[10] Only the characters' names remained the same; their costumes, locales, and identities were altered, and imaginative scientific explanations for their superpowers generally took the place of magic as a modus operandi in their stories.[13] Schwartz, a lifelong science fiction fan, was the inspiration for the re-imagined Green Lantern[14]—the Golden Age character, railroad engineer Alan Scott, possessed a ring powered by a magical lantern,[14] but his Silver Age replacement, test pilot Hal Jordan, had a ring powered by an alien battery and created by an intergalactic police force.[14]

In the mid-1960s, DC established that characters appearing in comics published prior to the Silver Age lived on a parallel Earth the company dubbed Earth-Two. Characters introduced in the Silver Age and onward lived on Earth-One.[15] It was established that the two realities were separated by a vibrational field that could be crossed, should a storyline involve superheroes from different worlds teaming up.[15]

Although the Flash is generally regarded as the first superhero of the Silver Age, the introduction of the Martian Manhunter in Detective Comics #225 predates Showcase #4 by almost a year, and at least one historian considers this character the first Silver Age superhero.[16] However, comics historian Craig Shutt, author of the Comics Buyer's Guide column "Ask Mister Silver Age", disagrees, noting that the Martian Manhunter debuted as a detective who used his alien abilities to solve crimes, in the "quirky detective" vein of contemporaneous DC characters who were "TV detectives, Indian detectives, supernatural detectives, [and] animal detectives."[17] Schutt feels the Martian Manhunter only became a superhero in Detective Comics #273 (Nov. 1959) when he received a secret identity and other superhero accoutrements, saying, "Had Flash not come along, I doubt that the Martian Manhunter would've led the charge from his backup position in Detective to a new super-hero age."[17] Unsuccessful attempts to revive the superhero archetype's popularity include Captain Comet, who debuted in Strange Adventures #9 (June 1951);[18] St. John Publishing Company's 1953 revival of Rocket Man under the title Zip-Jet; Fighting American, created in 1954 by the Captain America team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby; Sterling Comics' Captain Flash and its back-up feature Tomboy that same year;[19] Ajax/Farrell Publishing's 1954-55 revival of the Phantom Lady; Strong Man, published by Magazine Enterprises in 1955; Charlton Comics' Nature Boy, introduced in March 1956, and its revival of the Blue Beetle the previous year; and Atlas Comics' short-lived revivals of Captain America, the Human Torch, and the Sub-Mariner, beginning in Young Men Comics #24 (Dec. 1953).

Cartoon animal super-heroes were longer-lived. Supermouse and Mighty Mouse were published continuously in their own titles from the end of the Golden Age through the beginning of the Silver Age. Atomic Mouse was given his own title in 1953, lasting ten years, and Atomic Rabbit, later named Atomic Bunny, was published from 1955 to 1959. In England, the Marvelman series was published during the interregnum between the Golden and Silver Ages, substituting for the British reprints of the Captain Marvel stories after Fawcett stopped publishing the character's adventures.

Marvel Comics !!!!!!!!

DC Comics sparked the superhero revival with its publications from 1955 to 1960. Marvel Comics then capitalized on the revived interest in superhero storytelling with sophisticated stories and characterization.[20] In contrast to previous eras, Silver Age characters were "flawed and self-doubting".[21]

DC added to its momentum with its 1960 introduction of Justice League of America, a team consisting of the company's most popular superhero characters.[citation needed] Martin Goodman, a publishing trend-follower with his 1950s Atlas Comics line,note 1 by this time called Marvel Comics, "mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes," Marvel editor Stan Lee recalled in 1974. Goodman directed Lee to likewise produce a superhero team book, resulting in The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961).[22]

Under the guidance of writer-editor Stan Lee and artists/co-plotters such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel began its own rise to prominence.[8] With an innovation that changed the comic-book industry, The Fantastic Four #1 initiated a naturalistic style of superheroes with human failings, fears, and inner demons, who squabbled and worried about the likes of rent-money. In contrast to the straitlaced archetypes of superheroes at the time, this ushered in a revolution. With dynamic artwork by Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, and others complementing Lee's colorful, catchy prose, the new style became popular among college students who could identify with the angst and the irreverent nature of the characters such as Spider-Man, the X-Men and the Hulk during a time period of social upheaval and the rise of a youth counterculture. Comic book readers of the Silver Age were more scientifically-inclined than previous generations. Thus, comic books of the Silver Age explained superhero phenomenons and origins through science, as opposed to the Golden Age, which commonly relied on magic or mysticism.

Comics historian Peter Sanderson compares the 1960s DC to a large Hollywood studio, and argues that after having reinvented the superhero archetype, DC by the latter part of the decade was suffering from a creative drought. The audience for comics was no longer just children, and Sanderson sees the 1960s Marvel as the comic equivalent of the French New Wave, developing new methods of storytelling that drew in and retained readers who were in their teens and older and thus influencing the comics writers and artists of the future.[23]

Other publishers !!!!!!!

One of the top American comics publishers in 1956, Harvey Comics, discontinued its horror comics when the Comics Code was implemented and sought a new target audience.[24] Harvey's focus shifted to children from 6 to 12 years of age, especially girls, with characters such as Richie Rich, Casper the Friendly Ghost, and Little Dot.[24] Many of the company's comics featured young girls who "defied stereotypes and sent a message of acceptance of those who are different."[24] Although its characters have inspired a number of nostalgic movies and ranges of merchandise, Harvey comics of the period are not as sought after in the collectors' market as DC and Marvel titles.[24]

The publishers Gilberton, Dell Comics, and Gold Key Comics used their reputations as publishers of wholesome comic books to avoid becoming signatories to the Comics Code and found various ways to continue publishing horror-themed comics[25] in addition to other types. Gilberton's extensive Classics Illustrated line adapted literary classics, with the likes of Frankenstein alongside Don Quixote and Oliver Twist; Classics Illustrated Junior reprinted comic book versions of children's classics such as The Wizard of Oz, Rapunzel, and Pinocchio. During the late 1950s and the 1960s, Dell, which had published comics in 1936, offered licensed TV series comic books from Twilight Zone to Top Cat, as well as numerous Walt Disney titles.[26] Its successor, Gold Key — founded in 1962 Western Publishing started its own label rather than packaging content for business partner Dell — continued with such licensed TV series and movie adaptations, as well as comics starring such Warner Bros. Cartoons characters as Bugs Bunny and such comic strip properties as Beetle Bailey.[27]

With the popularity of the Batman television show in 1966, publishers that had specialized in other forms began adding campy superhero titles to their lines. As well, new publishers sprang up, often using creative talent from the Golden Age. Harvey Comics' Harvey Thriller imprint released Double-Dare Adventures, starring new characters such as Bee-man and Magic Master. Dell published superhero versions of Frankenstein, Dracula and the Werewolf.[26] Gold Key did licensed versions of live-action and animated superhero television shows such as Captain Nice, Frankenstein Jr. and The Impossibles, and continued the adventures of Walt Disney Pictures' Goofy character in Supergoof.[27] American Comics Group gave its established character Herbie a secret superhero identity as the Fat Fury, and introduced the characters of Nemesis and Magic-Man. Even the iconic Archie Comics teens acquired superpowers and superhero identities in comedic titles such as Archie as Capt. Pureheart and Jughead as Captain Hero.[28] Archie Comics also launched its Archie Adventure line (subsequently titled Mighty Comics), which included the Fly, the Jaguar, and a revamp of the Golden Age hero the Shield. In addition to their individual titles, they teamed in their group series The Mighty Crusaders, joined by the Comet and Flygirl join with three characters with their own titles. Their stories blended typical superhero fare with the 1960s' camp.[29]

Among straightforward Silver Age superheroes from publishers other than Marvel or DC, Charlton Comics offered a short-lived superhero line with characters that included Captain Atom, Judomaster, the Question, and Thunderbolt; Tower Comics had Dynamo, Mercury Man, NoMan and other members of the superhero espionage group T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents; and even Gold Key had Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom.

Underground commix !!!!!

According to John Strausbaugh of The New York Times, "traditional" comic book historians feel that although the Golden Age deserves study, the only noteworthy aspect of the Silver Age was the advent of underground comics.[4] One commentator has suggested that, "Perhaps one of the reasons underground comics have come to be considered legitimate art is due to the fact that the work of these artists more truly embodies what much of the public believes is true of newspaper strips — that they are written and drawn (i.e., authentically signed by) a single person."[30] While a large number of mainstream-comics professionals both wrote and drew their own material during the Silver Age, as many had since the start of American comic books, their work is distinct from what another historian describes as the "raw id on paper" of Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton.[31] Most often published in black-and-white with glossy color cover and distributed through counterculture bookstores and head shops, underground comics targeted adults and reflected the counterculture movement of the time,[31][32]

End and aftermath !!!!!!!

The Silver Age of comic books was followed by the Bronze Age.[33] The demarcation is not clearly defined, but there are a number of possibilities.

Historian Will Jacobs suggests the Silver Age ended in April 1970 when the man who had started it, Julius Schwartz, handed over Green Lantern — starring one of the first revived heroes of the era — to the new-guard team of Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams in response to reduced sales.[34] John Strausbaugh also connects the end of the Silver Age to Green Lantern. He observes that in 1960, the character embodied the can-do optimism of the era.[4] However, by 1972 Green Lantern had become world weary; "Those days are gone – gone forever – the days I was confident, certain ... I was so young ... so sure I couldn't make a mistake! Young and cocky, that was Green Lantern. Well, I've changed. I'm older now ... maybe wiser, too ... and a lot less happy."[4] Strausbaugh writes that the Silver Age "went out with that whimper."[4]

Comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg places the end of the Silver Age in June 1973, when Gwen Stacy, girlfriend of Peter Parker (Spider-Man) was killed in a story arc later dubbed "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", saying the era of "innocence" was ended by "the 'snap' heard round the comic book world — the startling, sickening snap of bone that heralded the death of Gwen Stacy."[33] Silver Age historian Craig Shutt disputes this, saying, "Gwen Stacy's death shocked Spider-Man readers. Such a tragedy makes a strong symbolic ending. This theory gained adherents when Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross' Marvels miniseries in 1994 ended with Gwen's death, but I'm not buying it. It's too late. Too many new directions — especially [the sword-and-sorcery trend begun by the character] Conan and monsters [in the wake of the Comics Code allowing vampires, werewolves and the like] — were on firm ground by this time."[35] He also dismisses the end of the 12-cent comic book, which went to 15 cents as the industry standard in early 1969, noting that the 1962 hike from 10 cents to 12 cents had no bearing in this regard.[35] Shutt's line comes with Fantastic Four #102 (Sept. 1970), Jack Kirby's last regular-run issue before the artist left to join DC Comics; this combines with DC's Superman #229 (Aug. 1970), editor Mort Weisinger's last before retiring.[36]

According to historian Peter Sanderson, the "neo-silver movement" that began in 1986 with Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? by Alan Moore and Curt Swan, was a backlash against the Bronze Age with a return to Silver Age principles.[37] In Sanderson's opinion, each comics generation rebels against the previous, and the movement was a response to Crisis on Infinite Earths, which itself was an attack on the Silver Age.[37] Neo-silver comics creators made comics that recognized and assimilated the more sophisticated aspects of the Silver Age.[37]

Legacy !!!!!

The Silver Age marked a decline in the prominence of American comics in genres such as horror, romance, teen and furry animal humor, or westerns, which were more popular than superhero adventures in the late 1940s through the mid-1950s, and fans of these genres see the Silver Age as a decline from that earlier era.[38]

An important feature of the period was the development of the character makeup of superheroes. Young children and girls were targeted during the Silver Age by certain publishers; in particular, Harvey Comics attracted this group with titles such as Little Dot. Adult-oriented underground comics also began during the Silver Age. Some critics and historians argue that one characteristic of the Silver Age was that science fiction and aliens replaced magic and gods.[39] Others argue that magic was an important element of both Golden Age and Silver Age characters.[40] Many Golden Age writers and artists were science-fiction fans or professional science-fiction writers who incorporated SF elements into their comic-book stories.[41] Science was a common explanation for the origin of heroes in the Silver Age.[42]

The Silver Age coincided with the rise of pop art, an artistic movement that used popular cultural artifacts, such as advertising and packaging, as source material for fine, or gallery-exhibited, art. Roy Lichtenstein, one of the best-known pop art painters, specifically chose individual panels from comic books and repainted the images, modifying them to some extent in the process but including in the painting word and thought balloons and captions as well as enlarged-to-scale color dots imitating the coloring process then used in newsprint comic books. An exhibition of comic strip art was held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs of the Palais de Louvre in 1967, and books were soon published that contained serious discussions of the art of comics and the nature of the medium.[43]

In January 1966, a live-action Batman television show debuted to high ratings. Like pop art, the show took comic-book tropes and re-envisioned them in the context of a different medium. Voiceover narration in each episode articulated the words of comic-book captions while fight scenes had sound effects like "Biff", "Bam" and "Pow" appear as visual effects on the screen, spelled out in large cartoon letters. Circulation for comic books in general and Batman merchandise in particular soared.[44] Other masked or superpowered adventurers appeared on the television screen, so that "American TV in the winter of 1967 appeared to consist of little else but live-action and animated cartoon comic-book heroes, all in living colour."[45] Existing comic-book publishers began creating superhero titles, as did new publishers. By the end of the 1960s, however, the fad had faded; in 1969, the best-selling comic book in the United States was not a superhero series, but the teen-humor book Archie.[46]

Artists !!!!!!!

Arlen Schumer, author of The Silver Age of Comic Book Art, singles out Carmine Infantino's Flash as the embodiment of the design of the era: "as sleek and streamlined as the fins Detroit was sporting on all its models."[4] Other notable artists of the era include Curt Swan, Gene Colan, Steve Ditko, Gil Kane, Jack Kirby and Joe Kubert.

Two artists that changed the comics industry dramatically in the late 1960s were Neal Adams, considered one of his country's greatest draftsmen,[47] and Jim Steranko. Both artists expressed a cinematic approach at times that occasionally altered the more conventional panel-based format that has been commonplace for decades.[citation needed] Adams' breakthrough was based on layout and rendering.[48] Best known for returning Batman to his somber roots after the campy success of the Batman television show,[47] his naturalistic depictions of anatomy, faces, and gestures changed comics' style in a way that Strausbaugh sees reflected in modern graphic novels.[4]

One of the few writer-artists at the time, Steranko made use of a cinematic style of storytelling.[48] Strausbaugh credits him as one of Marvel's strongest creative forces during the late 1960s, his art owing a large debt to Salvador Dalí.[4] Steranko started by inking and penciling the details of Kirby's artwork on Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. beginning in Strange Tales #151, but by Strange Tales #155 Stan Lee had put him in charge of both writing and drawing Fury's adventures.[49] He exaggerated the James Bond-style spy stories, introducing the vortex beam (which lifts objects), the aphonic bomb (which explodes silently), a miniature electronic absorber (which protected Fury from electricity), and the Q-ray machine (a molecular disintegrator)—all in his first 11-page story.[49]

Collectibility !!!!!!

A near-mint copy of Amazing Fantasy #15, the first appearance of Spider-Man, sold for $1.1 million to an unnamed collector on March 7, 2011.[50]

| Title | Issue | Cover date | Publisher | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazing Fantasy | 15 | 1962 Aug. | Marvel | First appearance of Spider-Man |

| Showcase | 4 | 1956 Oct. | DC Comics | First appearance of the Silver Age Flash |

| The Fantastic Four | 1 | 1961 Nov. | Marvel | First appearance of the Fantastic Four |

| The Amazing Spider-Man | 1 | 1963 Mar. | Marvel | Second appearance of Spider-Man, debut of his own series |

| The Incredible Hulk | 1 | 1962 May | Marvel | First appearance of the Hulk |

| The X-Men | 1 | 1963 Sept. | Marvel | First appearance of the X-Men and Magneto (comics) |

| Journey into Mystery | 83 | 1962 Aug. | Marvel | First appearance of Thor |

| The Flash | 105 | 1959 Mar. | DC Comics | Revival of Flash Comics, which ended with #104 (Feb. 1949) |

| Tales of Suspense | 39 | 1963 Mar. | Marvel | First appearance of Iron Man |

| The Brave and the Bold | 28 | 1960 Mar. | DC Comics | First appearance of the Justice League of America |